No other civilisation has enjoyed as long, continuous and intimate a history with jade as have the Chinese. Jade carvings survive both as objects of art and reliqueries and reflect the spiritual life of the Chinese civilisation.

Emperor Qianlong

Perhaps the greatest Imperial collector in China’s long history was the Emperor Qianlong (r.1736-95). Amongst other works of art, one of his great passions was jade and during his long reign he amassed a sizeable collection of antique and contemporary jades. During his reign there was an artistic peak of creativity of Chinese jade carving. Whilst the Emperor greatly admired Chinese carved jades, the jades for which he reserved his greatest praise were not Chinese but those carved in foreign lands.

The skill of Indian lapidaries had long been admired by the Chinese. Writings in Chinese texts from the Han period reveal that the inhabitants of Kashmir and the Gandhara region were especially skilled in carving and decorated their palaces with carved works of art.

In 1756, the Qianlong Emperor received a jade bowl from the Uyghur leader Khoja Burhan al-Din as a tribute gift. Over time more jades from Central Asian and India arrived at the Chinese court, capturing the attention of the Emperor. These jades became so highly regarded by the Qianlong Emperor that Chinese lapidaries working for the Chinese court were commissioned to make jade items imitating the ‘Hindustan’ style. Records of the Imperial Household also indicate that during the Qianlong reign (AD 1762) Muslim jade carvers were ordered to work at the ateliers of the Imperial palace in Beijing. Such was the near likeness of these jades that centuries later Chinese Scholars struggled to differentiate between the two.

The main source of nephrite jade for both Chinese and Indian lapidaries was the region of Khotan, in the Kunlun mountains, south of Xinjiang. Therefore, heavy boulders of this precious material would have been transported over considerable distances to the jade carvers of India and China. It took more than three years to transport jade boulders from its source to Beijing.

The Qianlong Emperor collectively termed Mongolian, Timurid and Indian jades as ‘Hindustan’ jades and such was his fascination with these foreign jades that in the scholarly text Tianzhu wu yindu kao e’ in 1768 AD, he wrote:

‘From Mount Dadak to the south is Kashmir, and to the west is Wendustan… Although Wendustan is Muslim, the Muslims have a legend that the remains of Buddha are there and have benefited from their common border with India. In the past it was perhaps Hindu, but now it is Muslim, it cannot be entirely ascertained. Wendustan and today’s Tangut land (i.e. China’s western border) and Muslim areas are all called Hindustan, probably the translators were in error in calling ‘Hindustan’ ‘Wendustan’, as both are similar to the sound in Indian.’

The Emperor’s admiration of Mughal, Ottoman and Timurid jades can be further witnessed in at least seventy-three appreciative poems he wrote about individual jades in the Imperial collection. One of the Emperor’s Imperial poems, state:

‘although Khotan produces both raw and carved jade, all the best carvings are from Hindustan’.

Jades of India

During the Mughal Dynasty (1526-1857) jade craftmanship from imperial workshops reached an apex during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628-1658). A jade vessel that once belonged to Emperor Shah Jahan, is currently on display at the Nehru Gallery at the V&A Museum, South Kensington, London. The vessel is composed of pure white nephrite jade sourced from Khotan and beautifully crafted by Indian lapidiary craftsmen’s at the Mughal imperial workshops.

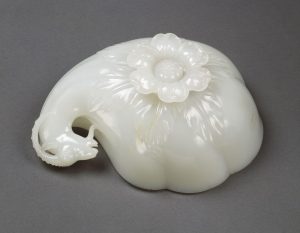

Mughal jades often featured flowers, leaves and sometimes animal shapes. They were flawless, extremely refined and had a shiny surface.

(IS.12-1962), V&A Museum, London.

While Chinese jades in ‘Hindustan’ style are indeed exquisite, it is clear from observing and handling them and from studying court records that they never achieved the craftmanship of the Indian jades.

Qianlong period, jade. Musée du Louvre, Paris

Some Key Differences between Mughal and Chinese carved Jades

Although the same basic techniques of jade carving were used by the Chinese and the Mughal lapidaries, research suggests that the northern Indian carvers used a bow lathe while seated on the ground, while the Chinese craftsmen used a treadle lathe while seated on a stool. Their choice and use of the raw material was also slightly different. While Chinese lapidaries admired natural inclusions of jade and incorporated these into their overall design, the Mughal carvers generally preferred jade of uniform colour.

Mughal carved jades are exceptionaly thin and the finest of the Indian jades are particularly noted for its transparent, translucent quality. Some Indian carved jades were so thinly carved by the Indian lapidaries that the Qianlong emperor described them as ‘supernaturally made’. Whereas the traditional Chinese reverence for jade is evidenced in the reluctance of Chinese lapidaries to cut jade to the extreme thinness of Indian jades.

Poetic Inscriptions

The Qianlong emperor was not only an avid collector he also enjoyed studying and composing commemorative poems about jade in his collection. Sixty-four of these poems are recorded in the Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji for Mughal and Mughal-style jades in the imperial collection dating between 1756 and 1794. Further, a number of poetic inscriptions were inscibed on the jade vessels. The National Palace Museum, Taipei has identified nineteen inscribed vessels in their collection, and six more in other collections.

On the emperor’s instructions a number of the poems were inscribed onto the jade objects. The early jade vessel sent as tribute by Burhan-al-Din in 1756 bears such an inscription and is currently in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taiwan. Another inscribed vessel the green jade bowl dated to 1771 is currently on display at the Louvre, Paris.

Visit:

National Palace Museum, Taiwan

Further Reading

Catalogue of a Special Exhibition of Hindustan Jade in the National Palace Museum, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1983

Excellent piece of research, beautifully written. thanks for sharing.

Beautifully written