The following article is based on a gallery lecture I gave at the Wallace Collection, London in November 2019, a unique collection of over 5500 exhibits housed at Hertford House, Manchester Square, London. Here, I attempt to follow the history and significance of jade as a hardstone material for Ottoman, Mughal Indian and Chinese hilts by looking at a few examples in the collection.

Ottoman Jade Hilts

The scholar Abu Rayan al-Biruni (973-1050) tells us in his 10th-11th treatise Kitab al–jamahir fi ma’rifat al jawahir (knowledge of precious stones) that the Eastern Turks decorated their swords, saddles, and belts with yashm, یشم (jade) as they believed that doing so ensured victory – a practice that was later followed by the Ottomans. It was additionally thought to ward off damage caused by lightning and thunderbolts.

Following the collapse of the Timurid dynasty in Samarqand and Herat in 1500 and 1506, it was Ottoman Turkey which appears to have become the main 16th century centre of Islamic jade-carving. This is despite its significant distance from the jade-producing region of Khotan and Kashgar which were closer to Persian courts where there was comparatively little imperial jade production.

Turkish decorated jade, in comparison to Mughal and Persian from the Islamic courts appears more angular. Often decorated with very dense arrangement of gold and gems resulting in a rich but somewhat barbaric effect that has often been referred to as ‘the opulent style.’ Stiff and formalised, instead of being set into the jade, the gems were held in small cylinders of gold projecting from circular plaques of gold foil on the surface of the stone. These plaques are chased to look like petals from which the gems rise as though enclosed by a golden calyx.

Another distinctively Ottoman type of inlay, which seems more common in the 17th century is a strictly formal arabesque with split palmettes, in which the gold is levelled with the surface of the jade without any surface engraving. A fine example of an Islamic dagger with an Ottoman Turkish jade hilt from the Wallace Collection can be seen above.

Jade carving in India 16th – 19th century

Jade carving in India can be dated to the reign of the Mughal Emperor Akbar (r.1556-1605) which is considered fairly recent for the establishment of what became a highly specialized art. It was during Akbar’s reign that a jade merchant introduced this beautiful material to the Mughal court from its source deep in Central Asia. Despite this there seem to be few examples of carved jades dating to Akbar’s reign.

It was Akbar’s son Prince Salim, later Emperor Jahangir (r.1605-1627) who is credited with the notable increase in production of beautifully carved jade objects in India. Jahangir was known to collect Ming Chinese jades as well as the jade vessels that belonged to his ancestors, the Timurids – which perhaps sparked his interest in instructing imperial workshops to create beautiful jade objects for his personal pleasure as well as gifts to Kings, princes and courtiers.

India, Mughal, 1620-25, Ink and opaque watercolor on paper

LACMA, Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection M.83.1.5

What we can be sure of is, that for the Timurid dynasty of Iran and Central Asia and their Mughal descendants in India, jade was a rare and valuable material. It can be assumed that part of Jahangir’s reason for collecting jade was to maintain this important dynastic link. Jade seemed to have become the hard-stone material of choice and was even fashioned into beautiful wine cups inscribed with poetry composed by the Mughal emperors. Such a fine appreciation of jade was naturally extended to jade daggers and sword hilts that were presented to noblemen.

Jahangir’s son, Emperor Shah Jahan (r 1628-1658) continued the tradition in jade carving. It was under his reign that perhaps the finest examples of jade carving were created. Best known for his great buildings notably the Taj Mahal he seemed to have favoured pure white jades, perhaps inspired by his extensive use of white marble in building projects. When Shah Jahan was in residence at Agra, Delhi, or Lahore, he regularly met with the craftsmen based at the imperial ateliers.

Jade artefacts continued to be produced under Emperor Aurangzeb, however towards the end of his rule a decline in artistic quality can be witnessed in the stereotyped forms of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that proliferate collections today.

Jade the medium

Mughal Indian jade objects are almost exclusively made of nephrite jade that were sourced from Kashgar in Central Asia. Nephrite jade is a silicate of calcium and magnesium, often with iron and other trace elements that give the stone various hues or striations.

Nephrite hardness 6.5, Diamond: 10, Rock crystal: 7 (Moh’s scale)

A long tradition of hard stone carving already existed in India and the Islamic courts of Iran and Central Asia. Craftsmen were experienced in making objects from hard stones like agate, carnelian and rock-crystal. Jade like other hard stones (rock crystal, agate) is a very difficult material to work with. As well as being hard, it is also fragile which means the craftsmen must deploy exceptional skill and patience when working with this material. Even the slightest slip of the workman’s tool would result in a hair-line crack in this precious material.

Technique of jade carving

In order to make a jade bowl you’d first need to find a boulder large enough for the carving process. The craftsmen would then use minerals harder than jade. These hard materials would be applied onto their tools in the form of sand, and the tools would then be used to grind the jade down. It would have been a very lengthy and difficult process.

Craftsmen were supervised by a head superintendent who would have directed the carving and surface decoration of hilts. Little is known about the artists and craftsmen of the imperial workshops, even the names are missing as few artefacts are signed.

White nephrite jade, agate, gold kundan inlay, rubies.

18th century dagger and mounts, Hyderabad, India.

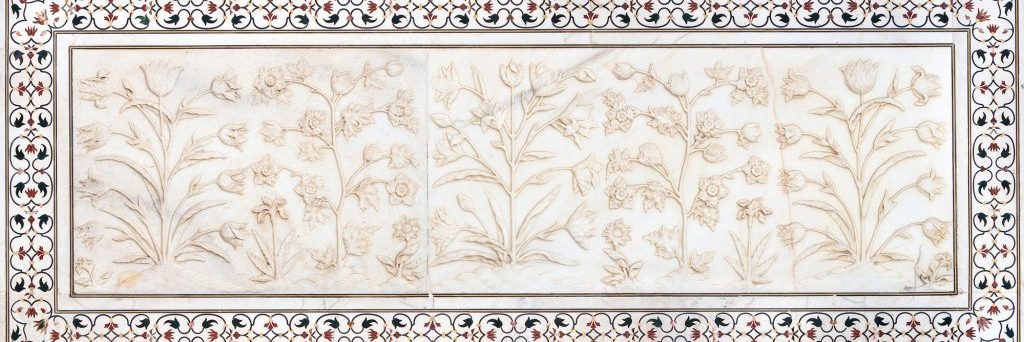

This translucent white jade selected for this hilt is often referred to as ‘mutton fat’. Perhaps inspired by falling autumn leaves, it has been decorated with autumnal shades of agate stone shaped into a pattern of delicate leaves, it is considered an exceptional example of hard stone carved jade and can be viewed at the Wallace Collection. The Taj Mahal at Agra was decorated with semi-precious stones that include jade may have inspired Mughal craftsmen to create this work of art.

Animal Jade Hilts

During Shah Jahan’s reign we begin to see a large quantity unadorned animal head-pommels. In fact many manuscripts and objects including jade are decorated and carved as such e.g parrot heads, lion head, horses heads. The following hilt may have been decorated with gold and precious stones at a much later date and place to enhance its value.

Incidentally, Mughal jade certainly reached the Royal Ottoman collection to serve as models for craftsmen and are still in Topkapi Saray today.

Chinese Jade Hilts

No other civilisation has such an enduring and intimate cultural history with jade as does China. Even today jade (Chinese: yù; 玉)is highly valued by the Chinese. It has many associations in China, with Confucius (551–479 BC) famously having likened its qualities to the most noble of human virtues.

Nephrite jade was the very first jade discovered in China and was the traditional jade used and carved since ancient times. The most important source was the Kunlun mountains, located in the town of Khotan (和田) in the Xinjiang province. Mines have been worked here for over a thousand years. White nephrite from the Kunlun Mountains occurs in a wide spectrum of colours. Green being the most common and ‘mutton fat’ or translucent white nephrite, considered the most desirable.

The above sword dated to the Q’ing dynasty is composed of a finely crafted Jade hilt in the Chinese style.

Further Reading;

Roger Keverne, Jade, 2000

Visit

Wallace Collection, Hertford Square, Manchester Square, London, W1U 3BN